Free City of Danzig

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

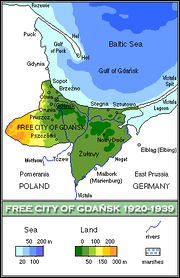

The Free City of Danzig (German: Freie Stadt Danzig; Polish: Wolne Miasto Gdańsk) was a semi-autonomous Baltic Sea port and city-state that was created on 10 January 1920, against the wishes of the local population [1] but in accordance with the terms of Part III, Section XI of the Treaty of Versailles of 1919. The Free City included the city of Danzig and over two hundred nearby towns, villages, and settlements, all of which had been a part of the former German Empire. As the League of Nations decreed, the region was to remain separated from the nation of Germany, as well as the newly-resurrected nation of Poland. The Free City was not autonomous; it was under League of Nations "protection" and put into a binding customs union with Poland. Poland also had other, special utilization rights towards the city.[2]

As the German invasion of Poland began, Danzig's government declared Danzig a part of Germany and the Free City was abolished. This occurred without the approval of Poland or the League of Nations. Widespread Anti-Semitic and anti-Polish discrimination and persecutions followed. Then, starting with the city's conquest by the Soviet Army in the early months of 1945, German citizens of the former Free City of Danzig were either expelled or killed, and the city was put under Polish administration by the Allied Potsdam Agreement. The city then took on its contemporary Polish name, Gdańsk, and Polish settlers were brought in to replace the native German population. The region was de-facto incorporated into the People's Republic of Poland and its status became final in regards to Polish sovereignty based upon the German Unification treaty of 1990.

Contents |

Establishment

Tradition of independence and autonomy

The city-state was denied the use of the term of Hanseatic City as part of its official name, which referred to Danzig's long-lasting membership in the Hanseatic League.[3]

Danzig had a long tradition of city-nation–like independence of its own. It was a leading player in the Prussian Confederation (Polish: Związek Pruski, German: Bund vor Gewalt, or colloquially Preußischer Bund) directed against the Teutonic Monastic State of Prussia. The Confederation stipulated with the Polish king, Casimir IV Jagiellon, that the Polish Crown will be invested - in personal union - with the role of head of state of western parts of Prussia, which became known as Royal Prussia (German: Königliches Preußen, Polish: Prusy Królewskie; to contrast with Ducal Prussia) (which remained a Polish fief). In return Casimir IV provided military support. Danzig, and the other cities, like Elbing and Thorn, financed most of the warfare and enjoyed a high level of city autonomy. Therefore Danzig took pride in using the title Royal Polish City of Danzig (Polish: Królewskie Polskie Miasto Gdańsk).

When, in 1569, Royal Prussia's Prussian estates (German: Landtag, Polish: Sejmik) agreed to incorporate into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by way of a real union, it was again Danzig, together with Thorn (Polish: Toruń) and Elbing (Polish: Elbląg), which insisted on preserving their special status. Danzig had to go through the costly Danzig Siege in 1577, but prevailed and got all its autonomy and privileges confirmed. To make clear its position about its special status, Danzig never used the opportunity to send its representatives to the Polish General Sejm, but always insisted on negotiating its issues by sending emissaries directly to the Polish king.

Territory

The Free City of Danzig (Gdansk) included the major city of Danzig (Gdańsk) as well as Zoppot (Sopot), Oliva (Oliwa), Tiegenhof (Nowy Dwór Gdański), Neuteich (Nowy Staw) and some 252 villages and 63 hamlets, covering a total area of 1,966 square kilometers (754 sq mi).

Polish rights declared by Treaty of Versailles

The Free City was to be represented abroad by Poland and was to be in a customs union with it. The German railway line that connected the Free City with newly-created Poland was to be administered by Poland, as well as all rail lines in the territory of the Free City. After local dockworkers had refused to unload ammunition supplies throughout the Polish-Soviet War in 1920,[4] the Westerplatte peninsula (until then a city beach), was also given to Poland to built up an ammunition dump and a military post within the city's harbour. There was also a separate Polish post office established, besides the existing municipal one.

League of Nations High Commissioners

Unlike Mandatory territories, which were entrusted to member countries, The Free City of Danzig (like the Territory of the Saar Basin) remained under the authority of the League of Nations itself, with representatives of various countries taking on the role of High Commissioner:[5]

| № | Name | Period | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Reginald Thomas Tower | 1919–1920 | |

| 2 | Edward Lisle Strutt | 1920 | |

| 3 | Bernardo Attolico | 1920 | |

| 4 | Richard Cyril Byrne Haking | 1921–1923 | |

| 5 | Mervyn Sorley McDonnell | 1923–1925 | |

| 6 | Joost Adriaan van Hamel | 1925–1929 | |

| 7 | Manfredi di Gravina | 1929–1932 | |

| 8 | Helmer Rosting | 1932–1934 | |

| 9 | Seán Lester | 1934–1936 | |

| 10 | Carl Jakob Burckhardt | 1937–1939 |

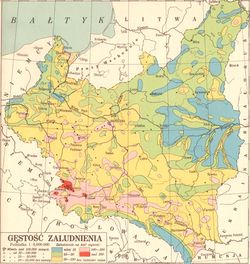

Population

The Free City had a population of 357,000 (1919), 95% of whom were Germans,[6] with the rest mainly either Kashubians or Poles.

The Treaty of Versailles, which had separated Danzig and surrounding villages from Germany, now required that the newly-formed state had its own citizenship, based on residency. German inhabitants lost their German Citizenship with the creation of the Free City, but were given the right within the first two years of the state's existence to re-obtain it; however, if they did so they were required to leave their property and make their residence outside of the Free State of Danzig area in the remaining part of Germany.[2]

As of 1924 54.7 % of the populace was Protestant and 34.5 % Catholic.[7] The Jewish community grew from 2,717 in 1910 to 7,282 in 1923 and 10,448 in 1929, many of them immigrants from Poland and Russia.[8]

| Nationality | German | German and Polish |

Polish, Kashub, Masurian |

Russian, Ukrainian |

Hebrew, Yiddish |

Unclassified | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Danzig | 327,827 | 1,108 | 6,788 | 99 | 22 | 77 | 335,921 |

| Non-Danzig | 20,666 | 521 | 5,239 | 2,529 | 580 | 1,274 | 30,809 |

| Total | 348,493 | 1,629 | 12,027 | 2,628 | 602 | 1,351 | 366,730 |

| Percent | 95.03% | 0.44% | 3.28% | 0.72% | 0.16% | 0.37% | 100.00% |

Politics

Government

| № | Name | Took office | Left office | Party |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presidents of the Danzig Senate | ||||

| 1 | Heinrich Sahm | 6 December 1920 | 10 January 1931 | None |

| 2 | Ernst Ziehm | 10 January 1931 | 20 June 1933 | DNVP |

| 3 | Hermann Rauschning | 20 June 1933 | 23 November 1934 | NSDAP |

| 4 | Arthur Karl Greiser | 23 November 1934 | 23 August 1939 | NSDAP |

| State President | ||||

| 5 | Albert Forster | 23 August 1939 | 1 September 1939 | NSDAP |

The Free City was governed by the Senate of the Free City of Danzig, which was elected by the parliament (Volkstag) for a legislative period of four years. The official language was German,[10] the usage of Polish was guaranteed by law.[11][12] The political parties in the Free City corresponded with the political parties in Weimar Germany; the most influential parties in the 1920s were the conservative German National People's Party, the Social Democratic Party of the Free City of Danzig and the Catholic Centre Party. A Communist Party was founded in 1921 with its origins in the Spartacus League and the Communist Party of East Prussia. Several liberal parties and Free Voter's Associations existed and ran in the elections with varying success. A Polish Party represented the Polish minority and received between 3% (1933) and 6% (1920) of the vote (in total, 4,358 votes in 1933 and 9,321 votes in 1920).[13] Initially the Nazi Party had only a small amount of success (0.8% of the vote in 1927) and was even briefly dissolved.[3]

Its influence grew with the onset of difficult economic times and the increasing popularity of the Nazi Party in Germany proper. Albert Forster became the Gauleiter in October 1930. The Nazis won 50 percent of votes in the Volkstag elections of 28 May 1933. They took over the Senate in June 1933, and Hermann Rauschning becoming President of the Senate of Danzig.

Rauschning was removed from his position by Forster and replaced by Arthur Greiser in November 1934.[14] He later appealed to the public not to vote for the Nazis in the 1935 elections.[3] Political opposition to the Nazis was repressed[15] and several politicians imprisoned and murdered.[16][17] The economic policy of the Nazi government, which increased the public issues for employment-creation programs,[18] and the retrenchment of financial aid by the German Government[19] led to a devaluation of more than 40 % of the Danziger Gulden.[20] The Gold reserves of the Bank of Danzig declined from 30 million Gulden in 1933 to 13 million in 1935 and the foreign asset reserve from 10 million to 250,000 Gulden.[21]

As in Germany, the Nazis introduced an "Enabling Act" and the racialist Nuremberg laws (November 1938),[22] existing parties and Unions were gradually banned. The presence of the League of Nations however still guaranteed a minimum of legal certainty. In 1935, the oppositional parties, except for the Polish Party, filed a law suit to the Danzig High Court in protest against the manipulation of the Volkstag elections.[3][14] The opposition also protested to the League of Nations, as did the Jewish Community of Danzig.[23][24]

The anti-Jewish riots of the Kristallnacht of 9/10 November 1938 in Germany were repeated by similar riots on 12/13 November.[14][25] The Danzig Great Synagogue was taken over and demolished by the local authorities in 1939.

German-Polish tensions

The rights of the Second Polish Republic within the territory of the Free City were stipulated in the Treaty of Paris of 9 November 1920 and the Treaty of Warsaw of 24 October 1921.[26] The details of the Polish privileges soon became a permanent matter of disputes between the local populace and the Polish State. While the representatives of the Free City tried to uphold the City’s autonomy and sovereignty, Poland sought to extend its privileges.[27]

Throughout the Polish–Soviet War local dockworkers went on strike and refused to unload ammunition supplies for the Polish Army. While the ammunition was finally unloaded by British troops,[28] the incident led to the establishment of a permanent ammunition depot at the Westerplatte and the construction of a trade and naval port in Gdynia,[29] which total exports and imports surpassed those of Danzig in May 1932.[30]

Several disputes between Danzig and Poland occurred in the sequel. The Free City protested against the Westerplatte depot, the placement of Polish letter boxes within the City[31] and the presence of Polish war vessels at the harbour.[32] The attempt of the Free City to join the International Labour Organization was rejected by the Permanent Court of International Justice at the League of Nations after protests of the Polish ILO delegate.[33][34]

Until June 1933 the High Commissioner decided in 66 cases of dispute between Danzig and Poland, in 54 cases one of the parties appealed to the Permanent Court of International Justice.[35] Subsequent disputes were resolved in direct negotiations between the Senate and Poland after both had agreed to abstain from further appeals to the International Court in Summer 1933 and bilateral agreements were concluded.[36]

In the aftermath of the German-Polish Non-Aggression Pact of 1934 the Danzig – Polish relations improved and Hitler instructed the local Nazi government to cease anti-polish actions.[37] In return Poland did not support the actions of the anti-Nazi opposition in Danzig and the Polish Ambassador to Germany, Józef Lipski stated in a meeting with Hermann Göring:[38]

..that a National Socialist Senate in Danzig is also most desirable from our point of view, since it brought about a rapprochement between the Free City and Poland, I would like to remind him that we have always kept aloof from internal Danzig problems. In spite of approaches repeatedly made by the opposition parties, we rejected any attempt to draw us into action against the Senate. I mentioned quite confidentially that the Polish minority in Danzig was advised not to join forces with the opposition at the time of elections.

When Carl J. Burckhardt became High Commissioner in February 1937 both Poles and Germans would have openly welcomed his withdrawal and Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs Józef Beck notified him not to “count on the support of the Polish State” in the case of difficulties with the Senate or the Nazi Party.[39]

While the Senate appeared to respect the agreements with Poland, the “Nazification of Danzig proceeded relentlessly”[40] and Danzig became a springboard for anti-polish propaganda among the German and Ukrainian minority in Poland.[41] The Catholic Bishop of Danzig, Edward O'Rourke, was forced to withdraw after he had tried to implement four additional Polish nationals as parish priests in October 1937.[42]

The German policy openly altered immediately after the Munich Conference in October 1938, when German Minister of Foreign Affairs, Joachim von Ribbentrop, demanded the incorporation of the Free City into the Reich.[43] In April 1939 High Commissioner Burckhardt was told by the Polish Commissioner-General that any attempt to alter its status would be answered with armed resistance on the part of Poland.[44]

Second World War and aftermath

World War II began with the shelling of the Westerplatte on 1 September 1939. Gauleiter Forster entered the High Commissioner's residence and ordered him to leave the City within two hours,[45] the Free City was formally incorporated into the newly-formed Reichsgau of Danzig-West Prussia. Polish civilian Post Office employees had been trained and had a cache of weapons, mostly pistols, three light machine guns and some hand grenades, when they defended the Polish Post Office for 15 hours. They were executed upon their surrender, against international law. The Polish military forces in the city held out until the 7th September.

Around 90% of the city was reduced to ruins towards the end of the Second World War. On 30 March 1945 the city was taken by the Red Army. It is estimated that more than 90% of the pre-war population were either dead or had fled by 1945. A number of inhabitants of the city perished in the sinking of a ship assisting evacuation, the Wilhelm Gustloff. It had up to 10,000 refugees on board at the time, including about 1,000 seriously wounded soldiers and sailors.

At the Potsdam conference the Allied Powers agreed that the former Free State was to become part of Poland. (The Yalta conference was unclear on this point).

By 1950, around 285,000 citizens of the former Free City were living in Germany and 13,424 citizens of the former Free City had been "verified" and granted Polish citizenship.[46] By 1947, 126,472 German-born Danzigers were expelled to Germany from Gdańsk, and 101,873 Poles from Central Poland and 26,629 Poles from Soviet-annexed Eastern Poland took their place.[46] As a result of this drastic population exchange, little consideration was given to the idea of reconstituting the Free City after the fall of the Iron Curtain.

In fiction

Historical Danzig forms the setting for much of Nobel Prize-winning author Günter Grass's acclaimed novel Die Blechtrommel (The Tin Drum).

See also

- Danzig Corridor

- Alfons Flisykowski

- Danzig Research Society

- History of Gdańsk

- Administrations of Danzig before April 1945

References

- ↑ John Brown Mason (1946). The Danzig Dilemma, A Study in Peacemaking by Compromise. Stanford university press. page 284.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Yale Law School. "The Versailles Treaty June 28, 1919: Part III". The Avalon Project. http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/imt/partiii.htm. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Matull, Wilhelm (1973). "Ostdeutschlands Arbeiterbewegung: Abriß ihrer Geschichte, Leistung und Opfer" (in German). Holzner. p. 419. http://library.fes.de/breslau/pdf/a20715/a20715_07.pdf.

- ↑ John Brown Mason (1946). The Danzig Dilemma, A Study in Peacemaking by Compromise. Stanford university press. http://books.google.de/books?id=ORWrAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA197&dq=westerplatte+league+of+nations+1920&lr=&as_brr=3&as_pt=ALLTYPES#PPA116,M1. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Danzig subsection of Poland entry from World Statesmen.org". http://www.worldstatesmen.org/Poland.htm#Danzig.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Year Book, 1938

- ↑ Die Freie Stadt Danzig(German)

- ↑ Bacon, Gershon C. (1980). Danzig Jewry:A short History. Jewish Museum (New York). p. 31. http://books.google.de/books?id=vvIECPYRssIC&pg=PA35&dq=freie+danzig&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=80#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ John Brown Mason (1946). The Danzig Dilemma, A Study in Peacemaking by Compromise. Stanford university press. http://books.google.de/books?id=ORWrAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA197&dq=westerplatte+league+of+nations+1920&lr=&as_brr=3&as_pt=ALLTYPES#PPA5,M1. Retrieved 2009-05-20.

- ↑ Lemkin, Raphael (1944 (reprint 2005)). Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. p. 155. http://books.google.de/books?id=y0in2wOY-W0C&pg=PA155&dq=free+danzig&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=9#v=onepage&q=free%20danzig&f=false.

- ↑ Constitution of Danzig (German)

- ↑ Matull, "Ostdeutschlands Arbeiterbewegung", page 419

- ↑ Die Freie Stadt Danzig, Wahlen 1919–1935 (German)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Sodeikat, Ernst (1966). "Der Nationalsozialismus und die Danziger Opposition" (in German). Institut für Zeitgeschichte. p. 139 ff. http://www.ifz-muenchen.de/heftarchiv/1966_2_2_sodeikat.pdf.

- ↑ Ratner, Steven R. (1995). The new UN peacekeeping. p. 94. ISBN 0-312-12415-5. http://books.google.de/books?id=0Rf9SE2YI-UC&pg=RA1-PA94&dq=free+danzig&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=65#v=onepage&q=free%20danzig&f=false.

- ↑ Sodeikat, p.170 ,p. 173, Fn.92

- ↑ Matull, "Ostdeutschlands Arbeiterbewegung", p. 440, 450

- ↑ *Burckhardt, Carl Jakob (in German). Meine Danziger Mission. p. 39.

- Lichtenstein, Erwin (1973) (in German). Die Juden der Freien Stadt Danzig unter der Herrschaft des Nationalsozialismus. p. 44.

- ↑ Loose, Ingo (2007) (in German). Kredite für NS-Verbrechen. Institut für Zeitgeschichte. p. 33. ISBN 978-3-486-58331-1. http://books.google.de/books?id=R2Dr9gdFZoAC&pg=PA34&dq=Danziger+Gulden+1935&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=1#v=onepage&q=Danziger%20Gulden%201935&f=false.

- ↑ Mason, John Brown (1946). The Danzig Dilemma. Stanford University Press. p. 74. http://books.google.de/books?id=ORWrAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_v2_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ Commercial Banks 1929-1934. League of Nations. 1935. p. LXXXIX. http://books.google.de/books?id=fQdXGT6tA8AC&pg=PR89&lpg=PR89&dq=Danziger+Gulden+1935&source=bl&ots=bt15gTLQIA&sig=AA1x3H6P6_kvb8vtclUyX9ZnfpM&hl=de&ei=j02GS8-GEdGlsQaF-qDODw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=8&ved=0CBoQ6AEwBzgy#v=onepage&q=Danzig&f=false.

- ↑ Schwartze-Köhler, Hannelore (2009) (in German). "Die Blechtrommel" von Günter Grass:Bedeutung, Erzähltechnik und Zeitgeschichte. p. 396. ISBN 978-3-86596-237-9. http://books.google.de/books?id=2nue91Rlg-0C&pg=PA396&dq=N%C3%BCrnberger+Gesetze+Danzig&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=2#v=onepage&q=N%C3%BCrnberger%20Gesetze%20Danzig&f=false.

- ↑ Kreutzberger, Max (1970) (in German). Leo Baeck Institute New York Bibliothek und Archiv. p. 67. http://books.google.de/books?id=vvCsfz67i1wC&pg=PA67&dq=freie+danzig&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=79#v=onepage&q=freie%20danzig&f=false.

- ↑ Bacon, Gershon C.. "Danzig Jewry: A Short History". Jewish Virtual Library. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Danzig.html.

- ↑ Grass, Günther; Mann, Vivian B.; Gutmann, Joseph (1980). Danzig 1939, treasures of a destroyed community. The Yewish Museum, New York. p. 33. http://books.google.de/books?id=vvIECPYRssIC&pg=PA35&dq=freie+danzig&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=80#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ Hannum, Hurst (1990). Autonomy, Sovereignty and Self-Determination. University of Pennsylvania. p. 375. http://books.google.de/books?id=gOq52_guRUoC&pg=PA375&lpg=PA375&dq=Christoph+M.+Kimmich+danzig&source=bl&ots=On4smA1wmY&sig=TH5-_SbhAKnO0AK7JFjLpODFVG8&hl=de&ei=86eUS4ThMJjEmwOK6MnwCw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CBQQ6AEwBDgK#v=onepage&q=Christoph%20M.%20Kimmich%20danzig&f=false.

- ↑ Stahn, Carsten (2008). The Law and Practice of International Territorial Administration. Cambridge University Press. p. 173 ff, 177. ISBN 978-0-521-87800-5. http://books.google.de/books?id=j6e16GCIfiEC&pg=PA184&dq=Danzig+Polish+german&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=93#v=onepage&q=Danzig%20&f=false.

- ↑ Hutt, Alan (1937). The Post-War history of the British Working Class. p. 38. http://books.google.de/books?id=XV35N74_jk8C&pg=PA38&dq=munitions+strike+Danzig&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=12#v=onepage&q=munitions%20strike%20Danzig&f=false.

- ↑ Buell, Raymond Leslie (1939). Poland – Key to Europe. p. 159. http://books.google.de/books?id=-KcfGbrKptoC&pg=PA159&dq=munitions+strike+Danzig&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=5#v=onepage&q=munitions%20strike%20Danzig&f=false.

- ↑ Eugene van Cleef, “Danzig and Gdynia,” Geographical Review, Vol. 23, No. 1. (Jan., 1933): 106

- ↑ worldcourts.com PCIJ, Advisory Opinion No. 11

- ↑ worldcourts.com PCIJ, Advisory Opinion No. 22

- ↑ worldcourts.com PCIJ, Advisory Opinion No. 18

- ↑ International Law Reports 1929-1930. H. Lauterpacht. http://books.google.de/books?id=KzYGaYaNswkC&pg=PA410&lpg=PA410&dq=International+Labour+Organization+danzig&source=bl&ots=pKvMXaQra1&sig=y5uVyd7y5bZCWkN_HMJX7icfPzc&hl=de&ei=HSCaSvTYK8WNsAawuaWiBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 2009-08-30.

- ↑ Hurst Hannum, page. 377

- ↑ Schlochauer, Hans J.; Krüger, Herbert; Mosler, Hermann (1960) (in German). Wörterbuch des Völkerrechts; Aachener Kongress – Hussar Fall. de Gruyter Verlag. p. 307, 309. ISBN 978-3-11-001030-5. http://books.google.de/books?id=EBSE1BF_w2AC&pg=PA309&dq=Danzig+Briefkasten&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ Hiden, John; Lane, Thomas; Prazmowska, Anita J. (1992). The Baltic and the Outbreak of the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. p. 74 ff, 80. ISBN 0-521-40467-3. http://books.google.de/books?id=HzrpExvg2XgC&pg=PA74&dq=Danzig+herbert+levine&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=4#v=onepage&q=Danzig%20herbert%20levine&f=false.

- ↑ Prazmowska, page 80

- ↑ Prazmowska, page 81

- ↑ Prazmowska, page 85

- ↑ Prazmowska, page 83

- ↑ Samerski, Stefan (2000). "Ein aussichtsloses Unternehmen – Die Reaktivierung Bischof Eduard Graf O’Rourkes 1939" (in German). p. 378. http://www.db-thueringen.de/servlets/DerivateServlet/Derivate-5265/SamerskiFsAdrianyi.pdf.

- ↑ Wasserstein, Bernard (2007). Barbarism and Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-19-873074-3. http://books.google.de/books?id=Pe6fSHkxEMMC&pg=PA280&dq=Danzig+League+of+Nations&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=90#v=onepage&q=Danzig%20&f=false.

- ↑ Woodward, E.L., Butler, Rohan, Orde, Anne, editors, Documents on British Foreign Policy 1919–1939, 3rd series, vol.v, HMSO, London, 1952:25

- ↑ Bleimeier, John Kuhn (1990). Hague Yearbook of International Law. Martinus Nijhoff Publ.. p. 91. ISBN 0-7923-0655-4. http://books.google.de/books?id=lJ43cLV8H7YC&pg=PA89&dq=Gauleiter+League+of+Nations&lr=&as_brr=3&cd=7#v=onepage&q=Gauleiter%20&f=false.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Bykowska, Sylwia (2005). "Gdańsk – Miasto (Szybko) Odzyskane" (in Polish). Biuletyn Instytutu Pamięci Narodowej 9–10 (56–57): 35–44. ISSN 1641-9561. http://www.ipn.gov.pl/portal/pl/24/1363/. Retrieved 2009-07-24.

External links

- Jewish community history

- History of Gdańsk / Danzig

- Gdańsk history

- Celebration of Gdańsk's centenary in 1997

- History & Hallucination, Wanderlust, Salon.com, January 5, 1998

- The power of Gdansk

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||